The nine billion names of God: revisited

Investigation #33 (The Materialist-Secularist Illusion 4)

I declare to you, brothers and sisters, that flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God, nor does the perishable inherit the imperishable. Listen, I tell you a mystery: We will not all sleep, but we will all be changed—in a flash, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed.—Corinthians 15:50-52, NIV

Allah’s Messenger said:

‘Allah has ninety-nine names, one hundred minus one, and whoever knows them will enter Paradise.’—54:23, Sahih Bukhari[1]

YEARS ago, I saw a video of writer, futurist, and inventor Arthur C. Clarke driving a hovercraft prototype in his garden. I was also fortunate enough to be given, through my father, an autographed copy of one of his non-fiction books. Clarke had predicted not only the communications satellite but the Internet. His work is groundbreaking and, apart from the legendary 2001: A space odyssey, he has written novels and short stories. One of his most renowned is the tale “The nine billion names of God”.[2] More so today, the story segues remarkably into contemporary astrophysics on the origin of the universe, and philosophy’s ever relevant cosmological argument (on the existence of the universe). It can also be seen as being linked to other significant discoveries in science (see “Darwinism: game over").

(This piece is the fourth in a series, the third of which is “Darwinism: game over”.)

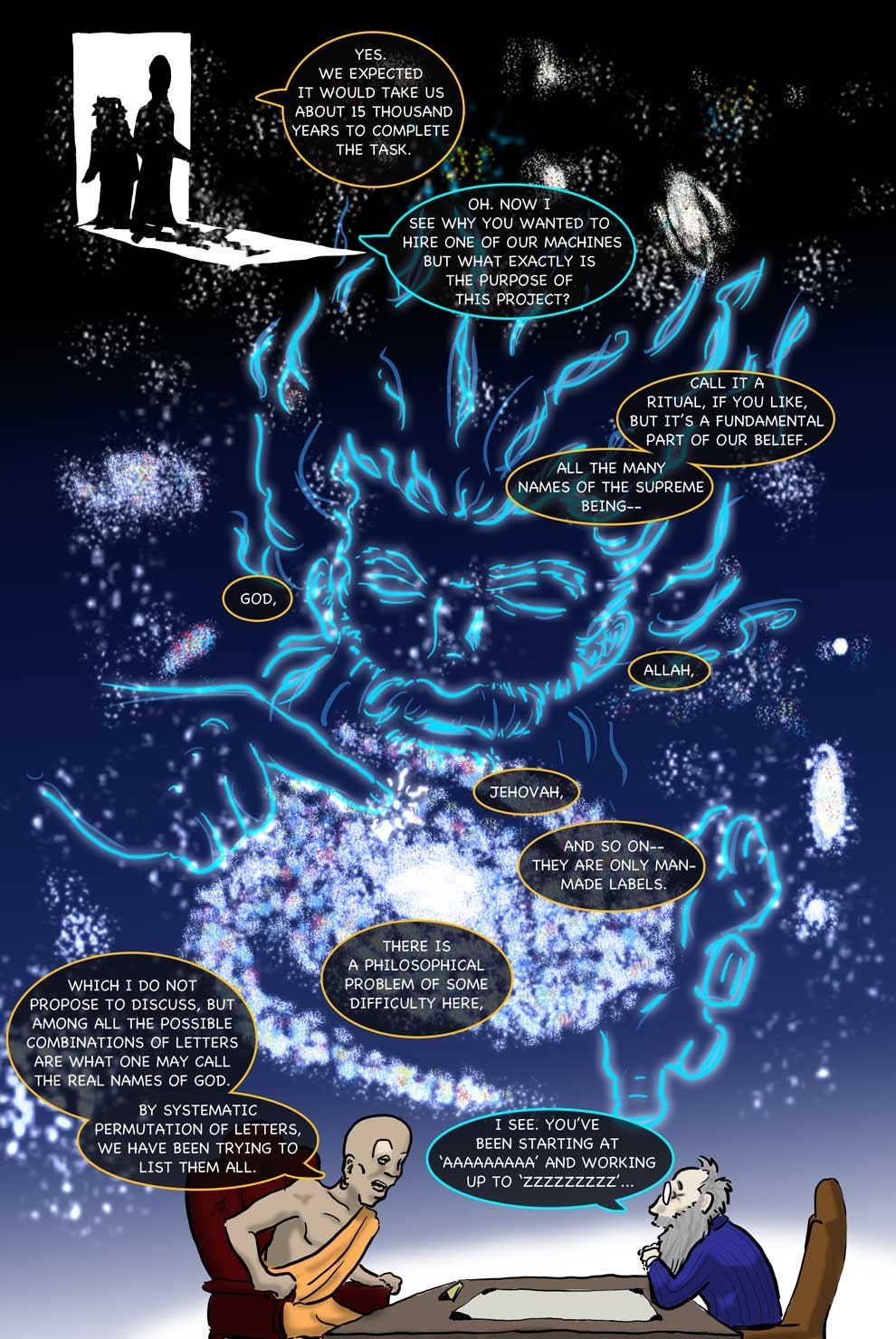

The science fiction story, published in 1953, involves a Tibetan lamasery renting an American advanced computer to calculate possible configurations of up to nine alphabetic letters of all the possible nine billion names of God. The process undertaken at the monastery has been going on for three centuries, and if continued by manually writing down combinations minus the nonsensical ones, it would take another 15,000 years to complete the list. The computer would finish the project in 100 days. Two computer specialists are sent with the machine to Tibet to do the job. Once the goal of listing the relevant names is achieved, the universe is supposed to end.[3] Finally, as the project nears completion the two sceptical American engineers leave the lamasery for the airfield where their transport awaits to take them home. But as they leave, they look up at the heavens only to see the stars being snuffed out.

There are many interpretations as to what the apocalyptic tale deals with. It must be remembered that the story was out when the Cold War was moving towards its peak and nuclear confrontation between the US/West and the USSR was a possibility. A sense of Armageddon prevailed: the implication that the complete listing of the names of God and its consequences in this context gives the piece a distinct eschatological resonance that would have struck home then. In these times of pandemics, so-called ‘post-truths’, and technological control of societies the tales’ end times theme has resurfaced its relevance.

Thus, one of the computer engineers finds out from the high lama the reason for completing the listing of the names which he imparts to his colleague:

‘[T]hey believe that when they have listed all His names — and they reckon that there are about nine billion of them — God’s purpose will be achieved. The human race will have finished what it was created to do, and there won’t be any point in carrying on. Indeed, the very idea is something like blasphemy…When the list’s completed, God steps in and simply winds things up... bingo!’

‘Oh, I get it. When we finish our job, it will be the end of the world.’

Chuck gave a nervous little laugh.

‘That’s just what I said…And do you know what happened? He [high lama] looked at me in a very queer way, like I’d been stupid in class, and said, “It’s nothing as trivial as that.”’

When humanity has reached a point of sufficient technological and spiritual advancement the nine billion names would be listed, and that would indicate that there was no need for the world to carry on. But why then do the monks hasten the listing of the names with the aid of a computer instead of allowing thousands of years more for the world to last by manual computation? The reaction of the high lama to Chuck over his comment that the completion of the names would “be the end of the world” is that such a statement was a trivialisation of Divine intention. Perhaps, what is meant is that the universe could shut down as one of its grand experiments, the human race and its progress, had reached its end; a new cycle could begin and beings would return to complete their journeys of self-realisation and unity with the Ultimate again. It seems to imply that the principal intelligent life in the universe is on earth; but given the content of the story before this, 1951’s “The Sentinel” which was an inspiration for 2001: it could also suggest that humanity was the last intelligent life form that had reached its apogee of advancement thereby showing the universe had completed its purpose.

(The Cold War context of the story and the possibility of nuclear war cannot be ignored. Due to the Korean War that started in 1950 and ended in 1953, the year the story was published, which led to the threat of nuclear weapons being used: the monks’ speeding up the the process of listing the nine billion names could be meant to precipitate the end of the universe so as to circumvent the increasing probability of global destruction by the wrongful use of technology through man’s folly. The end of the cosmos via Divine Will would at least be an act of salvation.)

The monks, being Buddhist, would extol non-attachment to the cycle of life/birth and death, and see obsession over it as a distraction laced with fear and desire. While Tibetan Buddhism is quite syncretic and does differ from other main branches of Buddhism (e.g. Mahayana and Theravada): it shares what is regarded as a tenet in Buddhism, that there is no Creator God as such. But according to some interpretations Buddhism is consistent with deism and theism at different levels, though this would be seen as controversial by some. Still, in Buddhism the end of the world is part of an unending process which sees another world-cycle (an aeon or kalpa) begin again. Clarke, though claiming to be atheistic was more an agnostic, and did seem inclined towards Buddhism (he lived in Sri Lanka from 1956 until his death, aged 90). Thus, in the story’s context involving Buddhist monks: the end of the world is only part of the start of the eventual rejuvenation of the universe; whereas in the case of the westerners who are portrayed as materialists despite technological advancement, such a finale is fearful and nihilistic.

‘Look,’ whispered Chuck, and George lifted his eyes to heaven. (There is always a last time for everything.)

Overhead, without any fuss, the stars were going out.— “The nine billion names of God”, Arthur C. Clarke.

However, it is quite synchronistic as to when Clarke’s tale appeared in relation to scientific discovery, as stated in an article from the National Library of Medicine:

In his story ‘The Nine Billion Names of God’ Arthur C. Clarke describes a Tibetan lama who approaches a computer engineering firm for help with a project that has kept his monastery busy for 300 years: compiling a list of all of the possible names of the Supreme Being…

Clarke published this story in 1953, the year that Watson and Crick modelled the double helix. It was oddly prescient of the Human Genome Project, that mad dash to sequence all 100 000 human permutations of the 4-letter alphabet of life &mdash% ATCG &mdash% by the year 2005 (that is, in 15, not 15 thousand, years). And now, ahead of schedule, with a computerized capacity to sequence 1000 letters of our genetic code per second, we pretty much have it: the spelling of our molecules, the 3 billion base pairs on which all physiologic processes, healthy or pathologic, are predicated…[4]

Indeed, as discussed in '“Darwinism: game over”, the DNA is encoded in a form of language or code and is indicative of a text (language) based universe similar in a sense to a computer programme; importantly, it implies an intelligence or mind in designing the human being. This is part of an advancement in scientific thinking known as Intelligent Design (ID) (author’s italics):

Intelligent design — often called ‘ID’ — is a scientific theory which holds that some features of the universe and living things are best explained by an intelligent cause rather than an undirected process such as natural selection. ID theorists argue that intelligent design can be inferred by finding in nature the type of information and complexity which in our experience arises from an intelligent cause.

Proponents of neo-Darwinian evolution contend that the information in life arose via blind, mechanistic processes that show no scientific evidence of guidance by intelligent design. ID proponents contend that the information in life does not appear to have an unguided origin, but arose via purposeful, intelligently guided processes. Both claims are scientifically testable using the standard methods of science. But ID theorists say that when we use the scientific method to explore nature, the evidence points away from blind material causes, and reveals intelligent design…

Contrary to what many might suppose, ID is much broader than the debate over Darwinian evolution. That’s because much of the scientific evidence for intelligent design comes from areas that Darwin’s theory doesn’t even address. In fact, much evidence for intelligent design comes from physics and cosmology.

The fine-tuning of the laws of physics and chemistry to allow for advanced life is a profound example of extremely high levels of CSI [complex and specified information] in nature. To give a few examples, the strength of gravity (gravitational constant) must be fine-tuned to within 1 part in 1035; the expansion rate of the universe be fine-tuned to within 1 part in 1055; and the cosmological constant must be fine-tuned to within 1 part in 10120. Cosmologists have calculated the initial entropy of the universe must have been fine-tuned to within 1 part in 1010^123. That’s ten raised to a power of 10 with 123 zeros after it — a number far too long to write out! The Nobel Prize-winning physicist Charles Townes observed: ‘Intelligent design, as one sees it from a scientific point of view, seems to be quite real. This is a very special universe: it’s remarkable that it came out just this way. If the laws of physics weren’t just the way they are, we couldn’t be here at all.’

Even the atheist cosmologist Fred Hoyle observed, ‘[a] common sense interpretation of the facts suggests that a super intellect has monkeyed with physics, as well as with chemistry and biology.’ From the tiniest atom, to living organisms, to the architecture of the entire cosmos, the fabric of nature shows strong evidence of intelligent design.[5]

It is extraordinary that Clarke, prescient as ever, uses a computer—as the most effective means to complete the listing of the names—to calculate the precise combinations to form the nine billion names of God. This reaffirms the mathematical objections to Darwinism in which the evolution/formation of living things had to occur via specific fine-tuned combinations within the basic and highly sophisticated cellular processes of beings (especially humans who also have remarkable mental abilities): none of which are possible through the mechanistic materialistic process of Darwin’s theory of evolution or natural selection. This is congruent to, and further reaffirms, the perfect mathematical fine-tuning of the universe as observed by many great scientists of the past as well as those in modern times.

The great mathematician fully, almost ruthlessly, exploits the domain of permissible reasoning and skirts the impermissible. That his recklessness does not lead him into a morass of contradictions is a miracle in itself: certainly it is hard to believe that our reasoning power was brought, by Darwin’s process of natural selection, to the perfection which it seems to possess…

The miracle of the appropriateness of the language of mathematics for the formulation of the laws of physics is a wonderful gift which we neither understand nor deserve.—“The unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences”, Eugene Wigner, Nobel Laureate, theoretical and mathematical physicist.

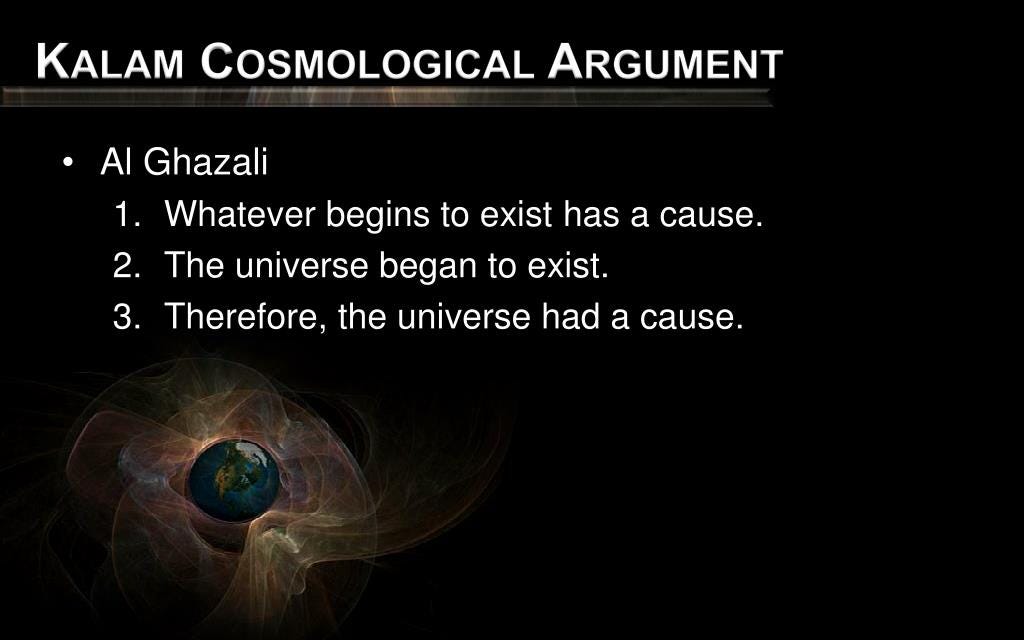

The connection of the calculation of letters to formulate the proper listing of the names of God implies the intelligence/mind behind the creation of the universe: it has a beginning and an end (as it ends when the list of the names are complete; or whatever that ends must have had a beginning). We know that the earth’s age is about 4 billion years, and that of the universe about 14 billion years. They certainly have a beginning. Intuitively, with clear thought, and advances in scientific knowledge, it is not difficult to conclude that there must be a purpose to existence, humanity, the world and the cosmos. And this ties in with the cosmological arguments in philosophy. Perhaps the most discussed in our time is the Kalām Cosmological Argument a key proponent being writer, Christian apologist, and theologian William Lane Craig.[6] Related to these matters is the central issue of the argument: does the universe have a beginning or does it have an infinite past? These are of great importance in contemporary astronomy as well, as it has been for many years.

As Craig explains about the Kalam:

Because of its historic roots in medieval Islamic theology, I christened the argument ‘the kalam cosmological argument’ (‘kalam’ is the Arabic word for medieval theology)…

Let’s allow one of the greatest medieval protagonists in this debate to speak for himself. Al-Ghazali was a twelfth century Muslim theologian from Persia, or modern-day Iran. He was concerned that Muslim philosophers of his day were being influenced by ancient Greek philosophy to deny God’s creation of the universe. After thoroughly studying the teachings of these philosophers, Ghazali wrote a withering critique of their views entitled The Incoherence of the Philosophers. In this fascinating book, he argues that the idea of a beginningless universe is absurd. The universe must have a beginning, and since nothing begins to exist without a cause, there must be a transcendent Creator of the universe.

In a more detailed work, Craig clarifies further:

In his Kitab al-Iqtisad [The Moderation in Belief], the medieval Muslim theologian Al-Ghazali presented the following simple syllogism in support of the existence of a Creator: ‘Every being which begins has a cause for its beginning; now the world is a being which begins; therefore, it possesses a cause for its beginning’... In defense of the second premise, Ghazali offered various philosophical arguments to show the impossibility of an infinite regress of temporal phenomena and, hence, of an infinite past. The limit at which the finite past terminates Ghazali calls ‘the Eternal’…which he evidently takes to be a state of timelessness. Given the truth of the first premise, the finite past must, therefore, ‘stop at an eternal being from which the first temporal being should have originated’.[7]

The issues are quite complex as there are many other premises, ideas and examples brought into play to show the robustness of the argument. Evidence cited include instances from astrophysics to strengthen claims. In his talk at Birmingham, “The Kalam Cosmological Argument”, Craig elaborated some of these points:

[Mathematicians and physicists] Arvind Borde, Alan Guth, and Alexander Vilenkin were able to show that any universe which is, on average, in a state of cosmic expansion throughout each history cannot be infinite in the past but must have a beginning. That goes for multiverse scenarios, too. In 2012 Vilenkin showed that models which do not meet this one condition still fail for other reasons to avert the beginning of the universe. Vilenkin concluded, ‘None of these scenarios can actually be past eternal’; ‘All the evidence we have says that the universe had a beginning.’

The Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem proves that classical space-time, under a single, very general condition, cannot be extended to past infinity but must reach a boundary at some time in the finite past. Now either there was something on the other side of that boundary or not. If not, then that boundary just is the beginning of the universe. If there was something on the other side, then it will be a region described by the yet-to-be discovered theory of quantum gravity. In that case, Vilenkin says, it will be the beginning of the universe. Either way, the universe began to exist.

This view seems to support the third premise of the Kalam, i.e. “Therefore, the universe had a cause”: but while Vilenkin, for example, is not committed to defending an Uncaused First Cause (he does not, claims agnosticism on this, and calls it a “mystery”), philosophically it is valid to infer an Uncaused First Cause—that transcends space-time as it creates space-time. That which is within space-time cannot be the cause of itself. Thus, this would make the cause something immaterial like a mind beyond space-time, and it would be an immeasurably powerful being; the initiator of all matter and energy. And this Cause must be a personal being: this explains the act of creation as one of free will, it is spontaneous and purposive; why else would there be a need to create the universe unless it was an act of will? The act of creation is a decision made. There are objections to the Kalam but they are effectively countered (a look at the links, and references provided will make this clear though the argument is still regarded by some as controversial). However, there is an objection to it from recent science that bears closer examination.

It is said that an argument is what convinces reasonable men and a proof is what it takes to convince even an unreasonable man. With the proof now in place, cosmologists can no longer hide behind the possibility of a past-eternal universe. There is no escape, they have to face the problem of a cosmic beginning.—Many Worlds in One, Alexander Vilenkin (cosmologist and professor in physics and astronomy).

This seeming objection comes from Nobel Laureate, mathematician, and mathematical physicist Sir Roger Penrose. In an interesting discussion between Penrose (an agnostic) and Craig, “The Universe: How did it get here & why are we part of it?”, interesting issues are raised. One of Penrose’s contributions to astrophysics is highlighting a conformal structure (based on conformal geometry) at a certain point in space-time where the end point of the universe is reached, and a singularity is created or an infinitely dense point in space-time, such as the centre of a black hole. This creates a point that leads to a Big Bang, and the start of a universe on the other side of the singularity. According to Penrose on what is behind or through the other side of this singularity in space-time:

…there was something on the other side and what [is it] to be something on the other side? And that is the Big Bang of a subsequent Aeon…and similarly our Big Bang was the continuation of the remote future of a previous Aeon; now I'm using the word ‘Aeon’, I looked up in the dictionary to make sure that the word Aeon didn't…mean a definite number of years, so I'm using it [as an unimaginably vast period of time].

What Penrose is referring to is his conformal cyclic cosmology [CCC] which has some evidence to support it.[8] This is a controversial matter and it has yet to be settled but Penrose and those working with him on this are updating their calculations and findings, and responding to objections. The point, however, is that in relation to the Kalam though it seems as if Penrose’s model is an objection to the argument, there are yet responses to this. Penrose brought the matter up in a discussion with the Vatican and he says:

…and they [Vatican] came up with what I thought was from their point of view the correct answer namely that, okay suppose this infinite succession of aeons is the correct explanation of the physical world: sure, God created the whole lot, and that…the temporal order of these things [is] not the important point; and I thought, yes, that from your perspective [Craig’s] that's the right answer.

This view is congruent, as Craig agrees, with the traditional Cosmological Argument as supported by important philosophers like Leibniz. However, Penrose’s point is that a Creator to the cosmos or physical world would be compatible with his CCC model. But Craig responds that it would still provide challenges to his Kalam argument not so much philosophically but in terms of evidence that would strain it: for the CCC seems to obviate an Uncaused First Cause as the Kalam (as it stands) affirms a single beginning to the universe rather than successive aeons even if the Divine is responsible for this process . There is, however, a way out that synthesises Penrose’s ideas and that of the Kalam.

In Buddhist doctrine, particularly the Theravada tradition, a central tenet is what is known as dependent origination wherein all of material existence is conditioned. In a continuous series of conditionality every aspect of existence/life arises contingently from another including the functioning of organisms, and mental states in humans—a view mirrored by what is accepted as fact in modern science; though there is still disagreement on the independence of mind as a separate entity from matter in scientific materialism (and certain philosophical viewpoints that reflect this). But Buddhism does posit that the universe has a beginning and an end as it is contingent (conditional), and there are some scientists who still try to resist this by believing in a beginningless universe (so as to avoid postulating a First Cause). However, the beginning of the cosmos according to Buddhism is apparently not a single event; there are innumerable world-cycles and each cycle is an aeon (reminiscent of Penrose), and a vast length of time. They begin and end in an ever-continual process. What is not posited is a Creator for the teachings focus on the Four Noble Truths: suffering, the cause of suffering, the end of suffering, and the path leading to the end of suffering. The actual cause of the start of universe and whether there is a Creator is something the Buddha remained silent on; there are various attempts to explain this including: that it was not relevant to his central doctrine on how to be released from the never-ending cycle of birth and death, and realise Nirvana. Another view is that not wanting to cause division between theists and atheists who would accept a teaching only if it fit with their preconceived notion of God’s existence, he remained silent on the matter, consistent with the pragmatic approach of traditional Buddhism.

Still, Buddhist cosmology would be consistent with Penrose’s CCC model. But what this cosmology implies is that the universe (known or measurable universe), or a series of them (Penrose refers to this as a ‘temporal order’), is being continually rejuvenated; it is space-time and matter that begins and ends, i.e, the creation and destruction of each universe one after the other: but that process of creation and destruction of universes in their ‘temporal order’ is beginningless and endless. It does not end in a ‘Big Crunch’ (at the end of the Big Bang) as a result of the universe expanding then collapsing back onto itself, then re-exploding again as another Big Bang ad infinitum; that theory has been debunked; the data does not corroborate it, it has been falsified.

Creation or the known/observable universe itself has a beginning and an end, and this makes it consistent with the Kalam as well (though not a single universe with only a single beginning and end to it). This raises the vital question of what then is there beyond the observable/measurable universe, or is that beyond comprehension?

Interestingly, Buddhist cosmology seems to posit a meta-universe or extra-dimensional space-time within, or from which, this cyclical start and end takes place eternally; this would be consistent with the contingency of matter, space-time. While science has not exactly postulated this, it has been touched on in Vedantic thought. There is a causal world of thought which surpasses the energetic and physical word. That such a world exists has been the basis of Platonic ideas, and is one of the three mysteries held by Penrose (see the links provided for Penrose, and “The theory of the three worlds”). To Penrose, the three worlds are interconnected; they would be rationalised by Mind containing the worlds thereby providing a coherent picture of these worlds, but Penrose says he does not see how this helps his work as a scientist: though not denying the metaphysical possibility of this (as in the discussion with Craig).

Notwithstanding, Buddhist cosmology still has to explain the start of the continuous physical space-time of the universe after it dissipates at the end of each aeon, and that would seem to be a First Cause. The Cosmological Argument, which could explain Penrose’s CCC as seen as a possibility in the discussion with Craig, is a possibility for Buddhism; but what is proposed is that Buddhist cosmology could work as a combination of CCC and the Kalam. Therefore, the cause of the start of the physical and space-time in each aeon is indeed a First Cause. The process takes place in a meta-universe analogous to the Vedantic causal world, and each aeon/world-cycle is the observable universe we, or other life, reside in when life is created/formed. This meta-universe is not similar to the multiverses that Craig refers to as criticism of those who propose it: as that only implies an infinite regress to the beginning of the universe without need for a First Cause which is an incoherent idea. What is proposed is a hypothetical timeless causeless dimension from which the Unconditioned First Cause initiates the act of creation (from the causal realm/world): the Big Bang, and all that follows, or the observable universe as we know it. It is that dimension that must exist as depicted in the Penrose diagram of the ‘never-ending story’ above, showing aeons and their crossovers. There is an extra-dimension, an Uncaused one in which this ever recurring expansion and crossover takes place of the observable universe, the universe as we know it: and an extra-dimensional Cause that initiates the eternal process of universes being created ‘past’, ‘present’, and ‘future’, each universe caused with a beginning and an end for each aeon.

At the end of one kalp [kalpa: world-cycle; aeon] all living beings merge into My primordial material energy. At the beginning of the next creation…I manifest them again. Presiding over My material energy, I generate these myriad forms again and again, in accordance with the force of their natures.—Bhagavad Gita: Chapter 9, Verse 7-8

Thus, the cause of the observable universe of matter and space-time would be the Uncaused First Cause: that in itself is beyond space-time and matter. Moreover, this would be consistent with the idea of Nirvana in Buddhism or Brahman in Hinduism: both are the Uncaused, Unborn, Uncreated, Unconditioned, Deathless, Beyond space-time, Ultimate Reality, Supreme Bliss; and Universal Mind or Consciousness (though the latter may be regarded as controversial in traditional Buddhism). This framework allows for a synthesis of the CCC and the Kalam to work.

Science can flourish only in an atmosphere of free speech.—Einstein

Clarke’s story is striking in even more ways in the context of subsequent scientific discovery and a re-examination of philosophical issues over the years. Central to this is the reaction of the high lama to Chuck’s comment (shared by George) that once the relevant names have been listed by the computer “it will be the end of the world”; his response is: “It’s nothing as trivial as that.” And indeed, it is not reflective of the triviality represented by the scientific materialist viewpoint that conflates with nihilism: that the end of everything is something to be feared. For most of the monks who are trained to be disinterested and free themselves as best they can via spiritual practices from clinging onto life and attachment to the senses, the end only reaffirms the end of that which is contingent, conditioned, subject to constant change and suffering. The end is initiated by the same Cause that created the beginning. The end of the variable is inevitable. But going beyond that, the hastening of the process triggered by listing the names using an advanced computer also indicates that a group of people (e.g. the monks) had reached a sufficient state of spiritual advancement (and progress in being able to use technology advantageously for a sacred purpose) so that one world-cycle of creation can end, and a new one eventually begin.

As usual, Clarke’s prescience results in his story dovetailing elegantly with Penrose’s CCC model as well as the Kalam. Pushing boundaries even further, yet again, science and spirituality prove that they are not mutually exclusive but complementary. We have reached a point where the world of the imagination, science, and philosophical thought are converging into a moment of synergy that has Intelligent Design at its core. Reaching this instance of intellectual and scientific development, a point or singularity of sorts, is indicative that the end of the old world imbued with the materialist-secularist illusion is about to be shattered by a Big Bang; that of a great spiritual awakening—that may one day be seen as the start of a Golden Age of learning, advancement, spirituality, and peace.

There is a certain sense in which I would say the universe has a purpose. It's not there just somehow by chance. Some people take the view that the universe is simply there and it runs along—it's a bit as though it just sort of computes, and we happen by accident to find ourselves in this thing. I don't think that's a very fruitful or helpful way of looking at the universe, I think that there is something much deeper about it, about its existence, which we have very little inkling of at the moment.—Roger Penrose

Working under My direction, this material energy brings into being all animate and inanimate forms…For this reason, the material world undergoes the changes (of creation, maintenance, and dissolution)…Those who know Me as unborn and beginningless, and as the Supreme Lord of the universe, they among mortals are free from illusion and released from all evils.—Bhagavad Gita, 9: 10; 10:3[9]

[P.S. Wishing all readers a meaningful New Year.]

End notes:

[1] Abu Huraira reported that Allah’s Messenger said:

There are ninety-nine names of Allah; he who commits them to memory will enter Paradise. Verily, Allah is Odd (He is one, and it is an odd number), and He loves odd numbers.—Book 48 Hadith 5, Sahih Muslim.

In Hindu numerology 9 is the number of Divine completeness, finality, and the number of the Creator of the universe: Brahma.

[2] The story can also be read here: “The nine billion names of God”. In an Author’s note to the 1967 edition, The Nine Billion Names of God: The Best Short Stories of Arthur C. Clarke, Clarke writes:

The title story was written, for want of anything better to do, during a rainy weekend at the Roosevelt Hotel. Its basic arithmetic was later challenged by J.B.S. Haldane, but I managed to save the situation by alphanumeric evasions whose precise nature now escapes me.

‘J.B.S.’ also remarked of this story, and ‘The Star’ (q.v.): ‘You are one of the very few living persons who has written anything original about God. You have in fact written several mutually incompatible things. If you had stuck to one thelogical [sic] hypothesis you might have been a serious public danger.’ I am glad of my self-contradiction, preferring to remain a prophet with a small p.

Nevertheless, I appear to have created a durable myth: not long ago, a radio talk on the BBC referred to the opening situation of this story as actual fact. And now that IBM computers have entered the field of biblical scholarship, perhaps this theme is coming a little closer to reality.

[3] The listing of the names per se is not the cause of the universe ending: it is that humanity having reached a point of technological advancement (which also implies the ability to misuse it) to successfully list all the names—and spiritual awareness that the purpose of the universe has been fulfilled as a result—there is no longer a need for the cosmos to carry on. This view is supported by an analogous theme in 1951’s “The Sentinel”—a basis for the film and novel 2001: A space odyssey. The discovery of a pyramidal structure on the moon, in the former, (a black monolith is found instead in the latter) indicates to a highly evolved extraterrestrial intelligence that humans have advanced sufficiently to master space travel, and are ready for some form of contact with life beyond earth; or start their further advancement as a species. However, in “The Sentinel” a sinister edge in the tone of its ending suggests the extraterrestrial life that will approach earth may not necessarily be friendly to humanity.

[4] See “Of genes and stars”. Ultimately, the name of the Uncaused First Cause is Unnameable as it surpasses conditionality and language, or the code/mathematics, that seems to underpin the cosmos. That nine billion names are needed to come close to a language based approximation in representing the Divine indicates the inadequacy of such a task in computing the immeasurable; yet human effort can yield results under Divine guidance though it is an ineluctable asymptote to actually describing, defining, or understanding All That Is.

[5] Hoyle’s full quote:

Would you not say to yourself, ‘Some super-calculating intellect must have designed the properties of the carbon atom, otherwise the chance of my finding such an atom through the blind forces of nature would be utterly minuscule. A common-sense interpretation of the facts suggests that a superintellect has monkeyed with physics, as well as with chemistry and biology, and that there are no blind forces worth speaking about in nature. The numbers one calculates from the facts seem to me so overwhelming as to put this conclusion almost beyond question.’

[6] A useful video: The Kalam Cosmological Argument | University of Birmingham, UK.

[7] See “The Kalam Cosmological Argument”, by William Lane Craig and James D. Sinclair, p101-201. The Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology. Edited by William Lane Craig and J. P. Moreland, 2009, Blackwell Publishing Ltd: UK.

For Craig’s response to some of the standard criticisms: Does William Lane Craig Misuse Science?

[8] For further information on Penrose’s ideas of the CCC, see this recent interview, “The Big Bang was not a beginning of the Universe”:

I have the view…that the Big Bang was not the beginning [it]… was followed from the remote future, it's a hard thing to get your mind around, this is why very few people take me seriously because you see it's telling that the very remote future, you see in the current view of current cosmology…the argument is that in a certain sense you see the inflationary picture…right after the big bang. There was expansion this enormous exponential expansion which increased the size of the universe by a huge factor within a tiny fraction of a second; now what I'm saying is that that is a misleading picture.

[T]hat that did not happen you have an exponential expansion but you're looking through the Big Bang to what happened before, and what happened before was this exponential expansion because it's just like what we see now in our Aeon, I use the word Aeon to describe from a Big Bang to the remote future so we had our Big Bang it's what currently people think is the whole of cosmology.

Also see “New evidence for cyclic universe claimed by Roger Penrose and colleagues”:

…Penrose, based at the University of Oxford , has developed a rival theory known as ‘conformal cyclic cosmology’ (CCC) which posits that the universe became uniform before, rather than after, the Big Bang. The idea is that the universe cycles from one aeon to the next, each time starting out infinitely small and ultra-smooth before expanding and generating clumps of matter. That matter eventually gets sucked up by supermassive black holes, which over the very long term disappear by continuously emitting Hawking radiation. This process restores uniformity and sets the stage for the next Big Bang.

For more see “Inside Penrose’s universe”.

[9] Quotes from the Bhagavad Gita:

Although I am the Creator and Sustainer of all living beings, I am not influenced by them or by material nature.—9:5

Bewildered by the material energy, such persons embrace demoniac and atheistic views. In that deluded state, their hopes for welfare are in vain, their fruitive actions are wasted, and their culture of knowledge is baffled.—9:12

[Top picture: “The nine billion names of God”, thissideofthetruth.]

© 2025 Sanjay Perera. All rights reserved.