Atonement: sacrifice as At-One-Ment with the Divine

Investigation #27 (The Materialist-Secularist Illusion 2)

To have a friend, to look at him, to follow him with your eyes, to admire him in friendship, is to know in a more intense way, already injured, always insistent, and more and more unforgettable, that one of the two of you will inevitably see the other die. One of us, each says to himself, the day will come when one of the two of us will see himself no longer seeing the other and so will carry the other within him a while longer, his eyes following without seeing, the world suspended by some unique tear, each time unique, through which everything from then on, through which the world itself-and this day will come-will come to be reflected quivering, reflecting disappearance itself.—Jacques Derrida, The Work of Mourning.

WHO would have thought that there would be a connection between The Hunger Games, the story of Abraham and Isaac in the Old Testament, and Derrida. Finally, I watched The Hunger Games including the recent prequel. But as synchronicity would have it, I had intended to write about Derrida’s The Gift of Death on finishing a tribute to a former teacher (see The Teacher).[1] However, it was upon completing the films that I saw the connection between all of them. And it was when I started to write this that I discovered the title of the haunting song at the end of the first film.[2] Derrida’s book focuses on the shocking call by God for Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac as an offering. It is an idea that has been discussed and written about endlessly; perhaps its most renowned examination is Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling. Indeed, it is the concept of sacrifice that intertwines all these works.

(This piece is the second of what may be a series of posts: see The Materialist-Secularist Illusion 1)

Notwithstanding, like most Hollywood productions The Hunger Games has a nihilistic core. Despite the important messages of the films, the central theme of sacrifice does not rise beyond the aesthetic or the ethical as Kierkegaard would define them. Broadly, the aesthetic would suggest the dramatic or romantic notions of sacrificing oneself for another; the ethical would imply that being willing to sacrifice for a righteous cause or for someone you care for is a good thing. And so, the series starts with the protagonist volunteering to go instead of her sister, whose name is called in a lottery, as a tribute to take part in mandatory gladiatorial games that involve youth killing one another to see who survives while it provides entertainment for the rulers and elite in the Capitol. The games themselves are meant to strike fear in the majority of the populace, and force their submission to the rulers so as to discourage rebellion. Unsurprisingly, the characters have Romanesque names; not only is the comparison between the world of the films and ancient Rome obvious: so is its reflection of contemporary society, our death-driven media and entertainment world.

As the films progress, the tributes try to save one another; they are willing to sacrifice themselves for those they learn to care for, and love, under most unexpected circumstances. The movies have an ethical dimension that do not transcend to the spiritual. It is seen as a good thing to save one another or to sacrifice yourself but why it is so, is unclear, as those who survive only live on in servitude, and the games continue with the outlying districts having to keep sending tributes each year. At the end of the first and fourth films two characters in the throes of a brutal death call upon the heroine to put them out of their misery. Mercy killing in that sense (another instance occurs early in the prequel) is in giving the gift of death. Life is meaningless and full of torment, and death just an extinguishing of suffering, there is not the slightest hope beyond that: the human fulfilment of having a family etc. is contingent upon the next tyrant and the coterie that supports him (or her, as shown as well), and whoever is willing to stand up to them in another cycle of violence. But that begs the issue as to why stand up to tyranny or do what is right, it all ends in nothingness: since all we are struggling towards is futility, and as Macbeth would say: “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

As the harsh President Coriolanus Snow, the nemesis of the films, says at the end of the third film (lines that are repeated at the end of the prequel): “It's the things we love the most that destroy us."

When the characters do their best to save someone whom they believe is worth helping to carry out their scheme for a successful rebellion against the Capitol, they walk into a trap that leads to near catastrophe for the heroine and their plans. This form of sacrifice for a group to undertake has nihilistic implications for even if aesthetically and ethically it leads to what can be termed a positive end, it only reveals that ultimately death is the final outcome for all that is living; and uncertainty of the future is all that can be guaranteed. There is no lasting spiritual salvation at the end of the trials and tribulations of existence, nor a context which gives substantial meaning to the suffering.

The message of much entertainment, and certainly the outpouring from Hollywood, is that of the materialist-secularist illusion; that life is a fight for survival, and we live to fight another day as we move inexorably along the way to dusty death. But Kierkegaard in his interpretation of Abraham’s dilemma shows that there is one more step beyond the ethical—the religious (spiritual is a better term) which defies logic or any form of rationality. There is no quid pro quo: the equation of giving my life for you so that you can carry on to hopefully do some good before your expiry date, and in doing so I believe I have done something good or shown my care or love for you—is meaningless in the highest state. Not that this selflessness is to be trivialised but it is not what can extricate the bind Abraham finds himself in.[3]

In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.—Aeschylus.

Derrida uses the Hebraic term korban to indicate sacrifice in relation to Abraham and Isaac. This is indeed the correct spiritual way to use ‘sacrifice’ for the term indicates a ‘drawing near to’, ‘becoming close to’ the Divine. But moving beyond Derrida, it is important to understand that the original meaning of ‘sacrifice’ itself implies to ‘make holy’ or offer something to bring us into proximity of the Divine. The word ‘atonement’ is one that ‘unites’ and ‘brings together’, connoting ‘At-One-Ment’ with the Divine. The term ‘attunement’ is a ‘bringing into harmony’, ‘adjusting to the same frequency’, ‘bring into sympathy’ with the Divine. As used here, ‘Atonement’ will indicate all the definitions above.

Before examining this further it must be noted that Derrida says the idea of sacrificing our lives for others does not qualify it as a gift in that we are not actually dying in lieu of the other: each person has to undergo their death as a unique experience, and no one can go through that for them. Sacrificing our life only delays the inevitable for the other.

I can give the other everything except immortality, except this dying for her to the extent of dying in place of her, so freeing her from her own death. I can die for the other in a situation where my death gives him a little longer to live; I can save someone by throwing myself in the water or fire in order to snatch him temporarily from the jaws of death; I can give her my heart in the literal or figurative sense in order to assure her of a certain longevity. But I cannot die in her place, I cannot give her my life in exchange for her death. [A]…mortal can give only to what is mortal, since he can give everything except immortality, everything except salvation as immortality.—The Gift of Death, Derrida.

The uniqueness of our birth is commensurate to that of our death, the difference is that as adumbrated by certain spiritual teachings: all that is created and formed, that which has a beginning and has an end, cannot last and is destined to decay. In the grand scheme of the universe, life and death are out our hands though we manipulate it and think we are in charge; but death is that reference point, that singular event horizon, that shows there are greater forces at work; it cannot be exchanged, bartered or avoided.

Everyone must assume their own death, that is to say, the one thing in the world that no one else can either give or take: therein resides freedom and responsibility…Even if one gives me death to the extent that it means killing me, that death will still have been mine, and as long as it is irreducibly mine I will not have received it from anyone else. Thus dying can never be borne, borrowed, transferred, delivered, promised, or transmitted. And just as it can’t be given to me, so it can’t be taken away from me.—The Gift of Death, Derrida.

The test that God gives Abraham is one of sacrifice, specifically that of atonement. Earlier he was asked to leave the comfort zone of his home: “The LORD had said to Abram, ‘Go from your country, your people and your father’s household to the land I will show you.’” (Genesis 12:1). This was the first sacrifice he was asked to make. The greatest was that of going through the act of absolute obedience to Divine Will in executing a plan to prepare his son for sacrifice. But he is then ordered by God to stop from carrying out the command just in time. This process was required as it was imperative for Abraham to go nearer to God in order to reap the blessings prepared for him and his descendants.

Atonement is never easy, it involves willingness to let go of those who are dear and important, or clinging on to certain objects, desires; to take that leap of faith. It brings us up close and personal to the Creator of the universe, All That Is, what can be called mysterium tremendum: that which is mysterious, awe-inspiring, and even precipitates terror for it is beyond human comprehension and sensibility (Kierkegaard would call it ‘fear and trembling’; and see end note [5] where ‘trembling with fear’ is also used in the Bhagavad Gita).

And why should we have to go through this? Because on the other side is mysterium fascinans which is the equally mysterious grace, peace, love and joy that comes from the even greater proximity to the Divine (and finally unity with it). The process is arduous and wrought with dangers but if steadfast in faith and spiritual practice, leads to freedom from suffering.[4]

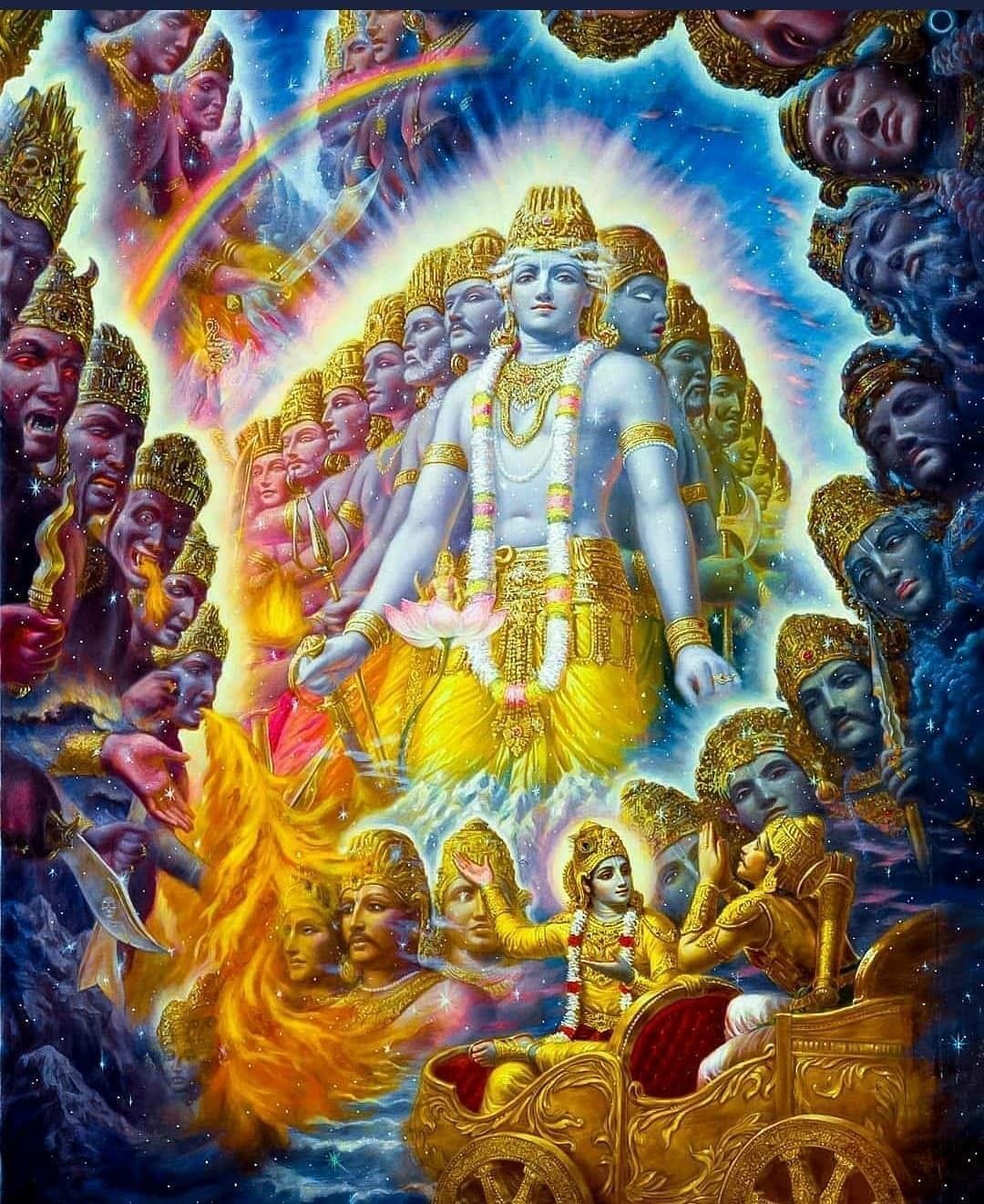

In a central Hindu text, the Bhagavad Gita, the greatest warrior of his clan Arjuna is granted a favour from Krishna (a Divine incarnation) acting as his charioteer on the battlefield, before engaging his relatives in a devastating conflict. The war was caused through the deceit and treachery of kinsman whom Arjuna had known since childhood; yet he cannot bear thinking he may have to kill them. Krishna says he has to consider the unthinkable and go through with it: this is his sacrifice, his atonement, his duty, his act of ultimate obedience to Divine Will. In order to work past the conundrums troubling him he has to act disinterestedly and surrender his actions as an act of faith and service to God. He must give up claim to wanting reward or to be fearful of the consequences of what he has to do; he is to focus his mind, heart, and soul on Divine Mercy and Grace—an immensely difficult challenge but there is no avoiding it to gain Liberation from the karmic cycle of birth and death.

To help him, Krishna takes on his original form; a supreme display of himself; and in a vision granted as Divine dispensation, as no being can see such a manifestation and survive, Arjuna witnesses what no mortal has been granted. The war does lead to a great slaughter between kith and kin. But the vision granted convinces Arjuna not to fear battle and the horrors that come from it if evil has to be defeated, for it is Divine Will that this happens to cleanse the world.

If the splendour of a thousand suns were to rise up at once in the sky, that would be like the splendour of that Mighty Being.

There in the body of the God of gods, the son of Pându then saw the whole universe resting in one, with its manifold divisions.

Then [Arjuna], filled with wonder, with his hair standing on end, bending down his head to the Deva in adoration, spoke with joined palms…

Arjuna said:… Thou art the Imperishable, the Supreme Being, the one thing to be known. Thou art the great Refuge of this universe;. Thou art the undying Guardian of the Eternal Dharma, Thou art the Ancient…—Bhagavad Gita, chapter 11.[5]

A prince and heir apparent of a kingdom in India Siddhartha Gautama, had to leave his family, wife and newly born son for a six-year intense painful struggle in search of Enlightenment. He tried all methods available from self-mortification to a farrago of spiritual practices till he found the middle way that led to transcending suffering, and the realisation of Nirvana (Liberation). In all these instances, a heavy cost is required for final emancipation from suffering and merger with the Divine. Finally, he was inadvertently given a meal of poisonous mushrooms by a follower; he endured his suffering patiently and when his karmic debt was paid went into a meditative state, and attained Nirvana as he gave up the body.[6] But what is the lesson for us in these examples going back to the case of Abraham and Isaac?

In various tests we are confronted with the process of atonement that requires great sacrifice. This concept is easier to understand within the framework of Hindu and Buddhist teachings in that reincarnation/rebirth are central to the journey of the spirit. Through countless births and deaths, the incalculably long path of atonement is taken on by many beings to find their way through a spiritual burning in the crucible of sacrifice of desires and attachments that lead to Divine surrender, and acceptance of Ultimate Reality. Abraham believed he would be provided for in undergoing the near sacrifice of his son, and he was, for a ram was given as a substitute for the sacrifice thereby sparing his son’s life. But what Abraham must have endured in the process not knowing how his faith would be redeemed we can only guess, but it must have been tormenting. There is no rational explanation for such a call to sacrifice one’s child but that is the leap of faith in which all modes of calculation fail upon confronting the non-rational, the Ultimate.

The loss of loved ones, family and friends, our own impending unique, irreplaceable, ineluctable demise happen in many instances beyond our understanding, expectations, rational mode of thinking; sometimes in a manner that shocks, horrifies, saddens, and calls into question our faith in everything when we see it in others, or when we are enduring it ourselves. But that is the thorny path of atonement that we have to tread. The examples of numerous prophets martyred to reach their manumission from birth and death (and still keeping their faith till the end), and the suffering filled journey of even incarnations of the Divine, are meant to inspire us that we can manage as well. Even Krishna had a tragic end after his clan declined into madness, ended fighting one another and destroying themselves; in the end, he was mistaken for a deer while resting in a forest, and killed by a hunter’s arrow. And the great warrior Arjuna having lost all his strength to fight later on, died with most of his brothers on a pilgrimage to the Himalayas in the cold.

These stories, and examples are there to let us know that we can complete our atonement as well whatever the burdens and challenges.

Even if you take this to have constant birth and death, you still don’t deserve to lament, O mighty armed! For, certain is death for the born and certain is birth for the dead; therefore, over the inevitable you should not grieve.—Bhagavad Gita.

The willingness of many to substitute themselves to save lives of loved ones only delays their end; and we do not know if those we loved and managed to save at the cost of ourselves would have met an even worse fate subsequently. Often as Derrida points out, we want to avoid being the ones to witness the loss of the other and live through the period left to us mourning, dealing with that loss. But the price of atonement is high, the closer we come into proximity of the Divine, the greater the sacrifice and endurance required.

Perhaps the most dramatic spiritual example is the crucifixion of Jesus, a horrific end indeed. Just as Abraham was called to show willingness to sacrifice his son, we are told that the Divine has his Son of Man transformed into the Son of God transfixed on the cross as a most visible display of atonement of what must be given up in the process of purification of clinging to the body, the sublunary, desires, attachment, and the inevitable fear that emanates from this.

Before his crucifixtion Jesus was plagued by doubt and fear in the garden of Gethsemane. And on the cross before his death he cries out to God thinking himself abandoned in his torment. But what follows later is his resurrection: breaking the cycle of birth and death permanently.

Then He said to them, “My soul is exceedingly sorrowful, even to death. Stay here and watch with Me.” He went a little farther and fell on His face, and prayed, saying, “O My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from Me; nevertheless, not as I will, but as You will.”—Matthew 26:38-39,

And being in agony, He prayed more earnestly. Then His sweat became like great drops of blood falling down to the ground.—Luke 22:44

And at the ninth hour Jesus cried out with a loud voice, saying, “Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?” which is translated, “My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?”—Mark 15:34, all quotes from New King James Version.

If such an atonement is called upon the Sons of God, then what is it that we expect in what we have to endure in our journey?

The end goal has been described in many ways but they are not always clear in a manner those of us schooled in worldly ideas expect; but it is the ineffable that is striven for.

There is, O Bhikkhus, an unborn, unoriginated, unmade and non-conditioned state. If, O Bhikkhus, there were not this unborn, unoriginated, unmade and non-conditioned, an escape for the born, originated, made, and conditioned, would not be possible here. As there is an unborn, unoriginated, unmade, and non-conditioned state, an escape for the born, originated, made, conditioned is possible.—The Buddha, Udāna and Itivuttaka.

Nibbana [is] bliss supreme.—The Buddha, Dhammapada.

Be anxious for nothing, but in everything by prayer and supplication, with thanksgiving, let your requests be made known to God; and the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard your hearts and minds through Christ Jesus.—Phillipians, 6-7

The act of atonement that Abraham undergoes is different from sacrifices characters make in The Hunger Games which is much like what we generally regard as sacrifice. Unintentionally, if we pray for an exchange between our fates and that of a loved one, so that the latter can carry on while we exit the scene: we have looked into the abyss of nihilism. The reasons may be laudable and ethical, and in our minds spiritually motivated; it may even be seen as a beautiful idea and act but it is not proper atonement. The genuine act of atonement is acceptance of what the outcome is, not that nothing should be done to help in a situation that may require it, but that when the inevitable occurs to come to grips (with great difficulty for most of us) with it and see what is beyond the loss of those we mourn for, even if the grieving lasts the rest of the remaining time left to us.

Abraham could have offered his life in exchange for Isaac by asking the Divine to strike him down and let his son live. But he has enough wisdom through his covenant with God to obey and not bargain with Him, and it is this act of unconditional faith that saves not only Isaac but bestows blessings on Abraham and his descendants. Kierkegaard’s Abraham takes a leap of faith into the religious/spiritual sphere by a suspension of ethical considerations when he starts to obey God’s order.

There is no calculus that we can conjure as in any form of offering of one’s own life/death as a gift to redeem another, even by the Sons of God; birth, life, death, and salvation are unique. The effort, the work must be put in, it is difficult, and seemingly insurmountable, there are no easy formulas or answers, and none can do the work for us: other than guide and be an example. Each must continue with the struggle as that is the individual covenant we have made with the Divine. No measurement or scale or negotiation can be used in prayer with the Immeasurable to replace another’s destiny when we have our own to fulfil. It is our responsibility within the liminal space of birth and death to strengthen that pact with the Divine, and honour the divinity inscribed on our hearts, mind, and spirit.

In understanding the surreal and irrational nature of existence and our lives, one in which so much is uncertain, conditioned, subject to sudden change; or as Hamlet says bedevilled by a “sea of troubles” and “the heart-ache, and the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to”: we come to try slowly and painfully, through a process of fear and trembling, to come close to All That Is. In all the striving and desire for love, affection, safety, security, freedom, perfect well-being, deathlessness, eternal joy and everlasting life, the end goal is the One in whom all needs, and tragedy ends. But arriving at that realisation through spiritual practice and divine surrender takes life times, and the overly rational mind and fear are stumbling blocks. But the way towards coming into resonance with the numinous has been lit many times by the representatives of Light, who through their own suffering show us never to fear the crosses we must bear on our unique paths that no one else can traverse but ourselves.

Existence can never be non-existence, neither can non-existence ever become existence. ... Know, therefore, that that which pervades all this universe is without beginning or end. It is unchangeable. There is nothing in the universe that can change [the Changeless]. Though this body has its beginning and end, the dweller in the body is infinite and without end.— Bhagavad Gita.

End notes:

[1] Derrida, Jacques. The Gift of Death (second ed.) & Literature in Secret; trans. David Wills, The University of Chicago Press, 2008.

[2] The song at the end of the first film, The Hunger Games, is called Abraham’s Daughter.

[3] Genesis 22, New King James Version:

Then God said, “Take your son, your only son, whom you love—Isaac—and go to the region of Moriah. Sacrifice him there as a burnt offering on a mountain I will show you…

Abraham took the wood for the burnt offering and placed it on his son Isaac, and he himself carried the fire and the knife. As the two of them went on together, Isaac spoke up and said to his father Abraham, “Father?”

“Yes, my son?” Abraham replied.

“The fire and wood are here,” Isaac said, “but where is the lamb for the burnt offering?”

Abraham answered, “God himself will provide the lamb for the burnt offering, my son.” And the two of them went on together.

When they reached the place God had told him about, Abraham built an altar there and arranged the wood on it. He bound his son Isaac and laid him on the altar, on top of the wood. Then he reached out his hand and took the knife to slay his son. But the angel of the Lord called out to him from heaven, “Abraham! Abraham!”

“Here I am,” he replied.

“Do not lay a hand on the boy,” he said. “Do not do anything to him. Now I know that you fear God, because you have not withheld from me your son, your only son.”

Abraham looked up and there in a thicket he saw a ram caught by its horns. He went over and took the ram and sacrificed it as a burnt offering instead of his son. So Abraham called that place The Lord Will Provide. And to this day it is said, “On the mountain of the Lord it will be provided.”

The angel of the Lord called to Abraham from heaven a second time and said, “I swear by myself, declares the Lord, that because you have done this and have not withheld your son, your only son, I will surely bless you and make your descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky and as the sand on the seashore. Your descendants will take possession of the cities of their enemies, and through your offspring all nations on earth will be blessed, because you have obeyed me.

[4] In The Idea of the Holy Rudolf Otto explores the concepts of mysterium tremendum and mysterium fascinans.

[5] Bhagavad Gita, chapter 11:

If the splendour of a thousand suns were to rise up at once in the sky, that would be like the splendour of that Mighty Being.

There in the body of the God of gods, the son of Pându then saw the whole universe resting in one, with its manifold divisions.

Then [Arjuna], filled with wonder, with his hair standing on end, bending down his head to the Deva in adoration, spoke with joined palms…

Arjuna said:… Thou art the Imperishable, the Supreme Being, the one thing to be known. Thou art the great Refuge of this universe;. Thou art the undying Guardian of the Eternal Dharma, Thou art the Ancient.

I see Thee without beginning, middle or end, infinite in power, of manifold arms; the sun and the moon Thine eyes, the burning fire Thy mouth; heating the whole universe with Thy radiance.

The space betwixt heaven and earth and all the quarters are filled by Thee alone; having seen this, Thy marvellous and awful Form, the three worlds are trembling with fear, O Great-souled One….

Be not afraid nor bewildered, having beheld this Form of Mine, so terrific. With thy fears dispelled and with gladdened heart, now see again this (former) form of Mine.

[6] Certain Buddhist traditions will deny that Nirvana (Nibbana), though consistent with the Hindu perspective, is the same as moksa (Ultimate Liberation); or that the Buddha was an incarnation of Divinity, and thereby a Son of God (as Jesus has been described): orthodox Buddhists, for e.g., tend to deny the existence of the soul or spirit, but this is a controversial point.

It is also understood that orthodox Christianity states Jesus’ crucifixtion redeemed everyone after that if they accepted him as the way to God. However, within a broader perspective, while redemption does take place for those who accept the Son of God and his teachings in that era, it is claimed that serious effort and discipline are needed for those beyond a certain time to progress along their path of atonement to attain salvation: belief alone in Christ is no guarantee of this, and many lives are needed before genuine spiritual liberation is realised.

[Top picture: Rembrandt.]

© 2024 Sanjay Perera. All rights reserved.